Python Fortran Rosetta Stone#

Python with NumPy and Fortran are very similar in terms of expressiveness and features. This rosetta stone shows how to implement many common idioms in both languages side by side.

How to Execute Code Snippets#

Consider for example the following code snippets:

In Python, just save the code to a file example.py and execute using

python example.py. In Fortran, save it to a file example.f90 and append the line

end at the end of the file (see the section Modules for more info

how this works). Compile using gfortran example.f90 and execute using

./a.out (you can of course add compilation options to gfortran, for

example to produce the executable with a different name).

Arrays#

Arrays are builtin in Fortran, and available in the NumPy module in Python. The usage is identical, except for the following differences:

Fortran counts (by default) from 1, NumPy always from 0

Fortran array sections (slices) include both ends, in NumPy the initial point is included, the final is excluded

In C the array is stored row wise in the memory (by default NumPy uses C storage), while in Fortran it is stored column wise (this only matters in the next two points)

By default

reshapeuses Fortran ordering in Fortran, and C ordering in NumPy (in both cases an optional argumentorderallows to use the other ordering). This also matters whenreshapeis used implicitly in other operations like flattening.The first index is the fastest in Fortran, while in NumPy, the last index is the fastest

By default NumPy prints the 2d array nicely, while in Fortran one has to specify a format to print it (also Fortran prints column wise, so one has to transpose the array for row wise printing)

Everything else is the same, in particular:

There is one-to-one correspondence between NumPy and Fortran array operations and things can be expressed the same easily/naturally in both languages

For 2D arrays, the first index is a row index, the second is the column index (just like in mathematics)

NumPy and Fortran arrays are equivalent if they have the same shape and same elements corresponding to the same index (it doesn’t matter what the internal memory storage is)

Any array expression involving mathematical functions is allowed, for example

a**2 + 2*a + exp(a),sin(a),a * banda + b(it operates element wise)You need to use a function to multiply two matrices using matrix multiplication

Advanced indexing/slicing

Arrays can be of any integer, real or complex type

…

from numpy import array, size, shape, min, max, sum

a = array([1, 2, 3])

print(shape(a))

print(size(a))

print(max(a))

print(min(a))

print(sum(a))

integer :: a(3)

a = [1, 2, 3]

print *, shape(a)

print *, size(a)

print *, maxval(a)

print *, minval(a)

print *, sum(a)

end program

from numpy import reshape

a = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], (2, 3))

b = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], (2, 3), order="F")

print(a[0, :])

print(a[1, :])

print()

print(b[0, :])

print(b[1, :])

integer :: a(2, 3), b(2, 3)

a = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], [2, 3], order=[2, 1])

b = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], [2, 3])

print *, a(1, :)

print *, a(2, :)

print *

print *, b(1, :)

print *, b(2, :)

end program

[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]

[1 3 5]

[2 4 6]

1 2 3

4 5 6

1 3 5

2 4 6

from numpy import array, size, shape, max, min

a = array([[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]])

print(shape(a))

print(size(a, 0))

print(size(a, 1))

print(max(a))

print(min(a))

print(a[0, 0], a[0, 1], a[0, 2])

print(a[1, 0], a[1, 1], a[1, 2])

print(a)

integer :: a(2, 3)

a = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], [2, 3], order=[2, 1])

print *, shape(a)

print *, size(a, 1)

print *, size(a, 2)

print *, maxval(a)

print *, minval(a)

print *, a(1, 1), a(1, 2), a(1, 3)

print *, a(2, 1), a(2, 2), a(2, 3)

print "(3i5)", transpose(a)

end program

(2, 3)

2

3

6

1

1 2 3

4 5 6

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]]

2 3

2

3

6

1

1 2 3

4 5 6

1 2 3

4 5 6

from numpy import array, all, any

i = array([1, 2, 3])

all(i == [1, 2, 3])

any(i == [2, 2, 3])

integer :: i(3)

i = [1, 2, 3]

all(i == [1, 2, 3])

any(i == [2, 2, 3])

from numpy import array, empty

a = array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

b = empty(10)

b[:] = 0

b[a > 2] = 1

b[a > 5] = a[a > 5] - 3

integer :: a(10), b(10)

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

where (a > 5)

b = a - 3

elsewhere (a > 2)

b = 1

elsewhere

b = 0

end where

end program

from numpy import array, empty

a = array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

b = empty(10)

for i in range(len(a)):

if a[i] > 5:

b[i] = a[i] - 3

elif a[i] > 2:

b[i] = 1

else:

b[i] = 0

integer :: a(10), b(10)

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

where (a > 5)

b = a - 3

elsewhere (a > 2)

b = 1

elsewhere

b = 0

end where

end program

from numpy import array, sum, ones, size

a = array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

print(sum(a))

print(sum(a[(a > 2) & (a < 6)]))

o = ones(size(a), dtype="int")

print(sum(o[(a > 2) & (a < 6)]))

integer :: a(10)

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

print *, sum(a)

print *, sum(a, mask=a > 2 .and. a < 6)

print *, count(a > 2 .and. a < 6)

end program

from numpy import array, dot

a = array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

b = array([[2, 3], [4, 5]])

print(a * b)

print(dot(a, b))

integer :: a(2, 2), b(2, 2)

a = reshape([1, 2, 3, 4], [2, 2], order=[2, 1])

b = reshape([2, 3, 4, 5], [2, 2], order=[2, 1])

print *, a * b

print *, matmul(a, b)

end program

[[ 2 6]

[12 20]]

[[10 13]

[22 29]]

2 12 6 20

10 22 13 29

from numpy import array, pi

a = array([i for i in range(1, 7)])

b = array([(2*i*pi+1)/2 for i in range(1, 7)])

c = array([i for i in range(1, 7) for j in range(1, 4)])

use types, only: dp

use constants, only: pi

integer :: a(6), c(18)

real(dp) :: b(6)

integer :: i, j

a = [ (i, i = 1, 6) ]

b = [ ((2*i*pi+1)/2, i = 1, 6) ]

c = [ ((i, j = 1, 3), i = 1, 6) ]

Some indexing examples#

First n elements:

Last n elements:

Select elements between i and j (inclusive):

Select n elements starting with index i:

Select elements between -n, …, n

(inclusive):

Loop over the whole array:

Loop between 3-th and 7-th elements (inclusive):

Split a string into three parts at indices i and j , the parts are:

Laplace update:

Modules#

Comparison of Fortran and Python import statements:

The following Python statements have no equivalent in Fortran:

Fortran modules work just like Python modules. Differences:

Fortran modules cannot be nested (i.e. they are all top level, while in Python one can nest the module arbitrarily using the

__init__.pyfiles)There is no Fortran equivalent of Python’s

import AOne can specify private module symbols in Fortran

Identical features:

A module contains variables, types and functions/subroutines

By default all variables/types/functions can be accessed from other modules, but one can change this by explicitly specifying which symbols are private or public (in Python this only works for implicit imports)

Symbols that are public don’t pollute the global namespace, but need to be explicitly imported from the module in order to use them

Importing a symbol into a module becomes part of that module and can then be imported from other modules

One can use explicit or implicit imports (explicit imports are recommended)

One creates the module:

And uses it from the main program as follows:

In Fortran, one can ommit the line program main, also one can just end

the file with end instead of end program. That way one can test any

code snippet just by appending end at the end.

In order to specify which symbols are public and private, one would use:

__all__ = ["i", "f"]

i = 5

def f(x):

return x + 5

def g(x):

return x - 5

module a

implicit none

private

public i, f

integer :: i = 5

contains

integer function f(x) result(r)

integer, intent(in) :: x

r = x + 5

end function

integer function g(x) result(r)

integer, intent(in) :: x

r = x - 5

end function

end module

There is a difference though. In Fortran, the symbol g will be private

(not possible to import from other modules no matter if we use explicit

or implicit import), f and i public. In Python, when implicit import

is used, the symbol g will not be imported, but when explicit import

is used, the symbols g can still be imported.

Floating Point Numbers#

Both NumPy and Fortran can work with any specified precision and if no precision is specified, then the default platform precision is used.

In Python, the default precision is typically double precision, while in Fortran it is single precision. See also the relevant Python and NumPy documentation.

In Fortran the habit is to always specify the precision using the _dp

suffix, where dp is defined in the types.f90 module below as

integer, parameter :: dp=kind(0.d0) (so that one can change the

precision at one place if needed). If no precision is specified, then

single precision is used (and as such, this leads to single/double

corruption), so one always needs to specify the precision.

In all Fortran code snippets below, it is assumed, that you did

use types, only: dp. The types.f90 module is:

module types

implicit none

private

public dp, hp

integer, parameter :: dp=kind(0.d0), & ! double precision

hp=selected_real_kind(15) ! high precision

end module

Math and Complex Numbers#

Fortran has builtin mathematical functions, in Python one has to import

them from the math module or (for the more advanced functions) from

the SciPy package. Fortran doesn’t include constants, so one has to use

the constants.f90 module (included below).

Otherwise the usage is identical.

Fortran module constants.f90:

module constants

use types, only: dp

implicit none

private

public pi, e, I

! Constants contain more digits than double precision, so that

! they are rounded correctly:

real(dp), parameter :: pi = 3.1415926535897932384626433832795_dp

real(dp), parameter :: e = 2.7182818284590452353602874713527_dp

complex(dp), parameter :: I = (0, 1)

end module

Strings and Formatting#

The functionality of both Python and Fortran is pretty much equivalent, only the syntax is a litte different.

In both Python and Fortran, strings can be delimited by either " or

'.

There are three general ways to print formatted strings:

print("Integer", 5, "and float", 5.5, "works fine.")

print("Integer " + str(5) + " and float " + str(5.5) + ".")

print("Integer %d and float %f." % (5, 5.5))

use utils, only: str

print *, "Integer", 5, "and float", 5.5, "works fine."

print *, "Integer " // str(5) // " and float " // str(5.5_dp) // "."

print '("Integer ", i0, " and float ", f0.6, ".")', 5, 5.5

And here are some of the frequently used formats:

Nested Functions#

Both Python and Fortran allow nested functions that can access the outer function’s namespace:

Use it like:

You can use the nested functions in callbacks to pass context:

def simpson(f, a, b):

return (b-a) / 6 * (f(a) + 4*f((a+b)/2) + f(b))

def foo(a, k):

def f(x):

return a*sin(k*x)

print(simpson(f, 0., pi))

print(simpson(f, 0., 2*pi))

real(dp) function simpson(f, a, b) result(s)

real(dp), intent(in) :: a, b

interface

real(dp) function f(x)

use types, only: dp

implicit none

real(dp), intent(in) :: x

end function

end interface

s = (b-a) / 6 * (f(a) + 4*f((a+b)/2) + f(b))

end function

subroutine foo(a, k)

real(dp) :: a, k

print *, simpson(f, 0._dp, pi)

print *, simpson(f, 0._dp, 2*pi)

contains

real(dp) function f(x) result(y)

real(dp), intent(in) :: x

y = a*sin(k*x)

end function f

end subroutine foo

And use it like:

Control flow in loops#

The common loop types in Python and Fortran are the for and do loops

respectively. It is possible to skip a single loop or to stop the

execution of a loop in both languages but the statements to do so

differ.

break and exit statements#

In Python, break is used to stop the execution of the innermost loop.

In Fortran, this is accomplished by the exit statement. For named

loops, it is possible to specify which loop is affected by appending its

name to the exit statement. Else, the innermost loop is interrupted.

Python’s exit() interrupts the execution of program or of an

interactive session.

continue and cycle statements#

Python’s continue statement is used to skip the rest of a loop body.

The loop then continues at its next iteration cycle. Fortran’s

continue statement does not do anything and one should use cycle

instead. For named loops, it is possible to specify which loop is

affected by appending its name to the cycle statement.

Examples#

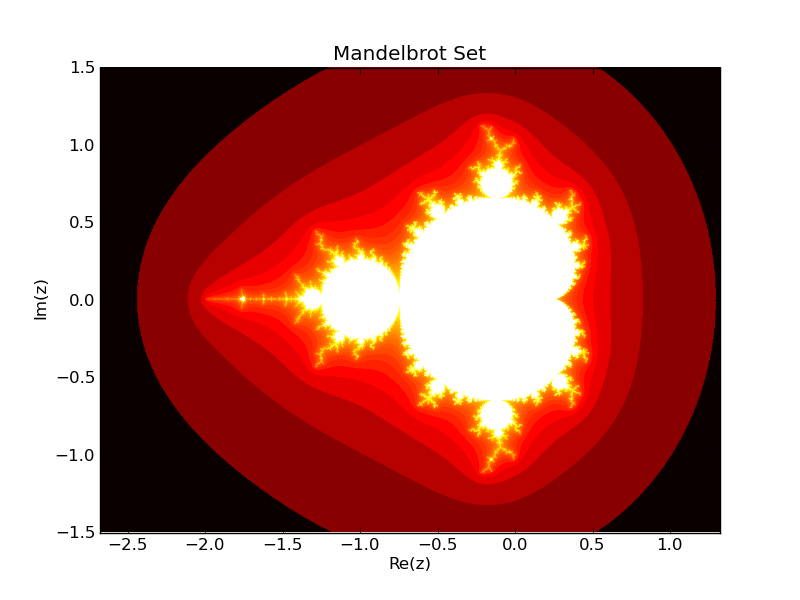

Mandelbrot Set#

Here is a real world program written in NumPy and translated to Fortran.

import numpy as np

ITERATIONS = 100

DENSITY = 1000

x_min, x_max = -2.68, 1.32

y_min, y_max = -1.5, 1.5

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(x_min, x_max, DENSITY),

np.linspace(y_min, y_max, DENSITY))

c = x + 1j*y

z = c.copy()

fractal = np.zeros(z.shape, dtype=np.uint8) + 255

for n in range(ITERATIONS):

print("Iteration %d" % n)

mask = abs(z) <= 10

z[mask] *= z[mask]

z[mask] += c[mask]

fractal[(fractal == 255) & (~mask)] = 254. * n / ITERATIONS

print("Saving...")

np.savetxt("fractal.dat", np.log(fractal))

np.savetxt("coord.dat", [x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max])

program Mandelbrot

use types, only: dp

use constants, only: I

use utils, only: savetxt, linspace, meshgrid

implicit none

integer, parameter :: ITERATIONS = 100

integer, parameter :: DENSITY = 1000

real(dp) :: x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max

real(dp), dimension(DENSITY, DENSITY) :: x, y

complex(dp), dimension(DENSITY, DENSITY) :: c, z

integer, dimension(DENSITY, DENSITY) :: fractal

integer :: n

x_min = -2.68_dp

x_max = 1.32_dp

y_min = -1.5_dp

y_max = 1.5_dp

call meshgrid(linspace(x_min, x_max, DENSITY), &

linspace(y_min, y_max, DENSITY), x, y)

c = x + I*y

z = c

fractal = 255

do n = 1, ITERATIONS

print "('Iteration ', i0)", n

where (abs(z) <= 10) z = z**2 + c

where (fractal == 255 .and. abs(z) > 10) fractal = 254 * (n-1) / ITERATIONS

end do

print *, "Saving..."

call savetxt("fractal.dat", log(real(fractal, dp)))

call savetxt("coord.dat", reshape([x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max], [4, 1]))

end program

To run the Python version, you need Python and NumPy. To run the Fortran

version, you need types.f90, constants.f90 and utils.f90 from the

Fortran-utils package. Both

versions generate equivalent fractal.dat and coord.dat files.

The generated fractal can be viewed by (you need matplotlib):

from numpy import loadtxt

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fractal = loadtxt("fractal.dat")

x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max = loadtxt("coord.dat")

plt.imshow(fractal, cmap=plt.cm.hot,

extent=(x_min, x_max, y_min, y_max))

plt.title('Mandelbrot Set')

plt.xlabel('Re(z)')

plt.ylabel('Im(z)')

plt.savefig("mandelbrot.png")

Timings on Acer 1830T with gFortran 4.6.1 are:

Python |

Fortran |

Speedup |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Calculation |

12.749 |

00.784 |

16.3x |

Saving |

01.904 |

01.456 |

1.3x |

Total |

14.653 |

02.240 |

6.5x |

Least Squares Fitting#

In Python we use Minpack via SciPy, in Fortran

we use Minpack directly. We first

create a module find_fit_module with a function find_fit:

from numpy import array

from scipy.optimize import leastsq

def find_fit(data_x, data_y, expr, pars):

data_x = array(data_x)

data_y = array(data_y)

def fcn(x):

return data_y - expr(data_x, x)

x, ier = leastsq(fcn, pars)

if (ier != 1):

raise Exception("Failed to converge.")

return x

module find_fit_module

use minpack, only: lmdif1

use types, only: dp

implicit none

private

public find_fit

contains

subroutine find_fit(data_x, data_y, expr, pars)

real(dp), intent(in) :: data_x(:), data_y(:)

interface

function expr(x, pars) result(y)

use types, only: dp

implicit none

real(dp), intent(in) :: x(:), pars(:)

real(dp) :: y(size(x))

end function

end interface

real(dp), intent(inout) :: pars(:)

real(dp) :: tol, fvec(size(data_x))

integer :: iwa(size(pars)), info, m, n

real(dp), allocatable :: wa(:)

tol = sqrt(epsilon(1._dp))

m = size(fvec)

n = size(pars)

allocate(wa(m*n + 5*n + m))

call lmdif1(fcn, m, n, pars, fvec, tol, info, iwa, wa, size(wa))

if (info /= 1) stop "failed to converge"

contains

subroutine fcn(m, n, x, fvec, iflag)

integer, intent(in) :: m, n, iflag

real(dp), intent(in) :: x(n)

real(dp), intent(out) :: fvec(m)

! Suppress compiler warning:

fvec(1) = iflag

fvec = data_y - expr(data_x, x)

end subroutine

end subroutine

end module

Then we use it to find a nonlinear fit of the form a*x*log(b + c*x) to

a list of primes:

from numpy import size, log

from find_fit_module import find_fit

def expression(x, pars):

a, b, c = pars

return a*x*log(b + c*x)

y = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31,

37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71]

pars = [1., 1., 1.]

pars = find_fit(range(1, size(y)+1), y, expression, pars)

print(pars)

program example_primes

use find_fit_module, only: find_fit

use types, only: dp

implicit none

real(dp) :: pars(3)

real(dp), parameter :: y(*) = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, &

37, 41, 43, 47, 53, 59, 61, 67, 71]

integer :: i

pars = [1._dp, 1._dp, 1._dp]

call find_fit([(real(i, dp), i=1,size(y))], y, expression, pars)

print *, pars

contains

function expression(x, pars) result(y)

real(dp), intent(in) :: x(:), pars(:)

real(dp) :: y(size(x))

real(dp) :: a, b, c

a = pars(1)

b = pars(2)

c = pars(3)

y = a*x*log(b + c*x)

end function

end program

This prints:

1.4207732655565537 1.6556111085593115 0.53462502018670921